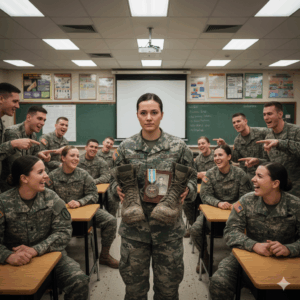

“Recruits Laughed at Her Old Boots — Until They Saw the Medal of Honor Inside.”

They called her “Grandma Boots” during her first week at boot camp. Her old boots—torn heels, faded color, frayed laces—looked like salvaged World War II gear. While other recruits showed off their brand-new combat boots, their new technology, the small girl with her low-cut hair quietly slipped on her old boots, every day.

The entire platoon laughed, including Lieutenant Barrett—who was known for her foul mouth: “Why don’t you go buy a new pair? Or do you want to retire on day one?” She simply replied, “They remind me why I’m here.” Rumors spread everywhere: she was poor, she was eccentric, she was trying to act special to get attention. But the truth was… no one knew her name, no one understood why her file said “recommended to be exempt from physical fitness,” something no one here had ever heard of.

Until the morning of the ninth, when Barrett suddenly made the entire platoon open all their personal belongings for inspection. When it was her turn, he yanked the shoes from their backpacks, intending to make a few jokes in front of the entire squad. But the insoles in the heels fell off—and the palm-sized metal thing slid out right into the middle of the floor.

The room fell silent.

No one moved.

Barrett bent down, and his face was pale.

In the torn shoes was a Medal of Honor, with a piece of paper bearing the name of its previous owner—a name that anyone who had studied military history would know.

The girl stood still, not showing off, not explaining. Just calmly saying one sentence that made the entire platoon stop in their tracks: “I don’t wear it… because I’m not worthy.”

And that was the moment everyone realized they knew nothing about her—especially when Lieutenant Barrett whispered, “No way… That person is…”

👉 The identity of the medal’s owner, and why it was in her shoe—is in the comments…

***************

They called her Grandma Boots from the minute she stepped off the bus.

The boots were a crime against regulation: leather cracked like drought earth, toes scuffed white, laces gray from too many washings. Everyone else had fresh-from-the-box Corcorans still smelling of factory plastic. She had these relics that looked older than she was. Nineteen, maybe twenty, tiny, hair chopped short like she’d done it herself with a bayonet, eyes the color of rain on concrete. She never gave her name. The roster just said “Trainee A. Morrow.” That was it.

Lieutenant Barrett spotted the boots on morning one and never let go.

“Jesus, Morrow, did you raid a museum on the way here? Those things belong in a display case, not on my grinder.”

The platoon laughed on cue. Barrett had a mouth that could strip paint.

Every day it was something new.

“Grandma Boots, you planning to shuffle your way through the obstacle course or just haunt it?”

“Grandma, you fall out again, I’m burying you in those antiques.”

She never answered back. Just laced them tighter, the frayed ends wrapped twice around her ankle like bandages, and kept moving. When someone asked why she didn’t buy new ones, she said, quiet enough that only the person next to her heard, “They remind me why I’m here.” Then nothing more.

Rumors filled the vacuum. Poor kid from some nowhere town. Trust-fund weirdo trying to cosplay hardship. Attention-seeker who thought vintage boots made her deep. The one thing nobody believed was the line on her medical file someone glimpsed when the clerk was careless: “Recommended exemption from all physical training—permanent.” In boot camp that was unicorn stuff. Nobody got a free pass unless they had one foot in the grave already. So of course they hated her more.

Day nine. Surprise wall-locker inspection. Barrett was in a mood—someone had short-sheeted his rack—and he decided to make an example.

“Empty your damn bags on the deck, let’s see what other garbage you people smuggled in.”

Duffels hit the floor. Socks, letters, contraband dip and energy drinks spilled everywhere. When they got to Morrow, Barrett snatched the boots himself, held them upside down like evidence in court.

“Behold, ladies and gentlemen, the museum pieces! Maybe there’s a Purple Heart in here too, right, Grandma? Let’s—”

He shook hard.

The right insole had been glued poorly decades ago. It flopped loose and something slid out—small, heavy, the color of dull gold—and rang once against the tile like a bell nobody wanted to hear.

Silence dropped so fast it hurt.

Barrett stared at the floor. The laughter died in fifty throats.

It was the Medal of Honor. Real one. Not a replica, not a morale patch—real star, real ribbon faded almost white, real light-blue field speckled with thirteen stars. The kind you only see behind bulletproof glass at Bragg or the Pentagon.

Tucked beneath it, folded so small it was almost invisible, a slip of onionskin paper. Barrett unfolded it with fingers that suddenly didn’t want to work.

The name typed there was Sergeant First Class Randall J. Morrow. Operation Red Wings II, Helmand Province, 2019. Posthumous.

The same last name as the girl standing barefoot on the cold tile.

Barrett’s mouth opened, closed, opened again. When he finally spoke it came out a whisper meant only for her but every recruit heard anyway.

“No way… You’re Randy Morrow’s kid?”

She didn’t flinch. Didn’t puff up with pride like they expected. She just looked at the medal on the floor the way you look at a coffin you’re not ready to close.

“I’m not worthy of it,” she said, voice flat, steady, loud enough for the whole bay. “He earned it saving eleven men after the bird went down. I haven’t saved anyone. Not yet. So I don’t wear it. I keep it where it has to hurt every step. When the boots finally fall apart, maybe then I’ll have done something worth carrying it in my hand instead of under my heel.”

She bent, picked up the medal like it burned, slipped it back into the hollowed-out heel along with the folded paper, and pressed the insole down with her thumb until the glue squeaked.

Barrett—Barrett who could make a drill sergeant blush—stood there holding two ancient boots like they were made of nitroglycerin.

The platoon didn’t laugh again. Ever.

That night, long after lights out, a few of them saw her on the fire escape, boots off, sitting with the medal in her bare palms, turning it over and over under the floodlight like she was trying to read braille no one else could see.

Nobody called her Grandma Boots after that.

They just called her Morrow.

And when she ran the three-mile assessment the next week—still in those same cracked boots—she finished first. By a lot.

No one was surprised.

News

A bankrupt Detroit diner owner gives away his final meal to a homeless stranger, thinking it means nothing

A bankrupt Detroit diner owner gives away his final meal to a homeless stranger, thinking it means nothing.Minutes later, black…

The first time Mrs. Higgins looked at me, she didn’t see a neighbor. She saw a problem

The first time Mrs. Higgins looked at me, she didn’t see a neighbor.She saw a problem. A man like me…

I never imagined a night behind the wheel would rewrite my entire life

I never imagined a night behind the wheel would rewrite my entire life. For three years, I drove Uber just…

My stepsister didn’t just try to steal my wedding day — she tried to erase me from it

My stepsister didn’t just try to steal my wedding day — she tried to erase me from it.And my parents…

She was forced to wash dishes at her wedding… simply because she was considered “POOR”—and then her millionaire husband showed up, paralyzing the entire ceremony

She was forced to wash dishes at her wedding… simply because she was considered “POOR”—and then her millionaire husband showed…

I drove Uber for three years just to survive—until one night, an old man asked my mother’s name, and everything I thought I knew about my life shattered

I drove Uber for three years just to survive—until one night, an old man asked my mother’s name, and everything…

End of content

No more pages to load