The rain came down in sheets, hammering the corrugated roof of the Fort Ironwood changing hut like machine-gun fire. It was 0408, pitch-black outside, and the only light inside came from two flickering fluorescent tubes that made everyone look half-dead. I sat on the wooden bench in the corner, unlacing my boots with the same slow, deliberate movements I’d used for twenty years. Water dripped from my black hair onto the concrete floor. My coveralls were soaked through, clinging to the scars most people never notice.

Twenty years as a SEAL does that to you. You learn to move like you have all the time in the world, because sometimes a single extra second is the difference between living and becoming a closed-casket ceremony nobody talks about.

The three of them came in laughing, still high on the adrenaline of finishing the log-pt evolution an hour ahead of the rest of the platoon. Ramirez, Kowalski, and big-mouth Delaney—nineteen, twenty, twenty-one years old. Babies with buzz cuts and egos the size of aircraft carriers. They’d been riding me for six straight weeks.

“Hey, Grandma,” Delaney called, peeling off his blouse and tossing it at my feet. “You kiss the log goodnight when we left you behind?”

Ramirez snorted. Kowalski just grinned like a hyena.

I didn’t answer. I never did. Silence is a weapon most kids their age have never learned to respect.

They circled closer. I could smell the cheap energy drinks on their breath and the testosterone leaking out of their pores. Delaney kicked my boot. “I said, do you kiss it goodnight, Grandma?”

I pulled the second boot off, set it neatly beside the first. My socks were soaked, but I took the time to roll them down anyway. Old habits.

Ramirez stepped in from the left. “Maybe she’s deaf.”

Kowalski from the right. “Or just slow.”

Delaney leaned down until his face was inches from mine. “Or maybe she’s just useless.”

That word. Useless.

I’ve heard it before. In a lot of languages. Usually right before someone tried to put a bullet in me.

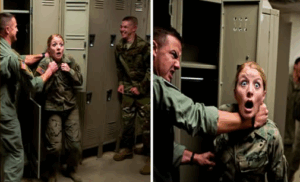

Delaney grabbed the front of my coveralls and hauled me up. I let him. Forty years old, five-foot-six, maybe a hundred thirty pounds dripping wet. To them I was a pushover. To them I was the weak link the instructors kept in the course for diversity numbers.

They had no idea.

Delaney shoved me back against the lockers. The metal was cold through my wet shirt. “Say something, Grandma.”

I looked up at him. Calm. Breathing through my nose. Counting heartbeats the way they teach you in SERE school when someone’s about to waterboard you for practice.

Ramirez moved in behind me, pinned my arms. Kowalski cracked his knuckles like he’d seen in movies. Delaney smiled the way only bullies smile when they think they’ve already won.

Then his hands went to my throat.

Not a choke yet. Just resting there. Threatening. His thumbs pressed lightly against my windpipe. “Last chance,” he whispered. “Apologize for slowing us down, and maybe we let you breathe.”

I felt Ramirez tighten his grip on my wrists. Felt Kowalski shift his weight, ready to drive a knee into my back if I struggled.

Three against one. Outnumbered. Outmassed. Perfect.

I met Delaney’s eyes.

And smiled.

It wasn’t a nice smile.

The room changed temperature in less than a heartbeat.

Delaney felt it first. His fingers hesitated.

I moved.

Left foot slid back six inches—textbook base. My hips dropped an inch, weight on the balls of my feet. Ramirez still thought he had my arms. He didn’t. I rotated my wrists outward against his thumbs—the weakest part of any grip—and broke his hold like snapping twigs. Before he could react, I drove my right elbow straight back into his solar plexus. Not hard enough to rupture anything permanent, just enough to empty every molecule of air from his lungs.

He folded with a sound like a deflating balloon.

Kowalski was already swinging. Big, looping haymaker from a kid who’d never been in a real fight. I stepped inside it, caught his wrist, pivoted, and used his own momentum to slam him face-first into the lockers. The clang echoed like a church bell. I kept hold of the arm, twisted until the shoulder popped out of socket with a wet click. He screamed. I let him drop.

Delaney tried to backpedal, hands still half-raised from where they’d been around my throat. His eyes were wide now, pupils blown. The predator had become prey and he hadn’t caught up yet.

I didn’t give him time.

Two quick steps, left hand clamped over his mouth before he could yell, right hand already at his carotid. Not squeezing—just resting there. Letting him feel how easy it would be. How little effort it would take to put him to sleep for a good ten minutes.

His pulse hammered against my fingers like a rabbit’s.

I leaned in close enough that he could smell the salt water still on my skin from the bay crossing we’d done at 0200.

“Listen very carefully,” I whispered, voice low and flat—the same voice I’d used in a dozen countries when I needed someone to understand that death was now an option. “You just committed felony assault on a federal officer. I could end your careers right now. I could end a lot more than that.”

His knees started to shake.

“But I won’t,” I continued. “Because you’re children. And children can be taught.”

I released his carotid but kept the hand over his mouth. With the other I reached down, picked up my neatly folded towel, and pressed it gently against the small cut on his eyebrow where the locker had kissed him.

“You’re going to pick up your friends,” I said. “You’re going to get them to medical. You’re going to tell the corpsman you fell during night movement. And tomorrow, when the instructors ask why your shoulders are taped and your pride is broken, you’re going to look them in the eye and say, ‘Because we learned respect the hard way.’”

I took my hand off his mouth.

He didn’t speak. Just nodded, frantic.

I stepped back.

The three of them scrambled—Ramirez wheezing, Kowalski cradling his arm, Delaney half-carrying both of them toward the door. They didn’t look back.

When the door slammed behind them, the hut was silent except for the rain.

I sat down on the bench again, picked up my socks, and finished rolling them off. My hands weren’t even shaking.

Twenty years of muscle memory doesn’t care about age.

I thought about the missions that never made the news. The nights in the Hindu Kush when we moved like ghosts. The time in Fallujah when I carried a wounded teammate three miles through streets full of people who wanted us dead. The submarine that surfaced off some coast I’m still not allowed to name so we could pull two hostages out of a compound that officially didn’t exist.

I thought about the medals in a box somewhere that no one will ever see.

And I thought about the instructors who’d asked me—quietly, respectfully—why a woman with my record was volunteering to go through this meat grinder again at forty years old.

I never gave them the real answer.

Because some lessons can only be taught by someone who looks like the weakest person in the room.

I pulled on dry socks, laced my spare boots, and stood up.

Outside, the rain was still falling. Inside, three recruits were learning that the world is bigger and scarier than they ever imagined.

And somewhere in the dark, a forty-year-old “Grandma” walked back to the barracks with her head high and her hands clean.

Fort Ironwood would remember this night for a long time.

So would they.

News

Police Officer Flatlines as 20 Doctors Declare Him Dead – Until His K9 Partner Breaks In, Tears the Sheet Away, and Sniffs Out the Hidden Bite That Saved His Life.

I remember the exact moment everything went black. One second I was standing in my kitchen, pouring coffee for the…

Navy SEAL Dad Loses Hope After 9 Hours of Searching for His Kidnapped Son – Until an 8-Year-Old Girl and Her Bleeding Dog Say: “We Know Where He Is”

The freezing night air clawed at my lungs as I stood in the command tent, staring at the glowing map…

Cadets Mock & Surround ‘Lost Woman’ in Barracks for a Brutal ‘Welcome’ – Then She Disarms Them All and Drops the Navy SEAL Bomb.

I stepped off the Black Hawk at dusk, the rotors still thumping echoes across the Virginia training compound. My duffel…

Three Cocky Marines Shove a Quiet Woman in a Club – Then the Entire Room Snaps to Attention and Their Faces Turn Ghost-White.

The bass thumped through the floor like artillery fire, vibrating up my legs as I stood at the edge of…

Admiral Jokingly Asks Janitor for His Call Sign – The Two Words That Made a Navy Legend Freeze in Horror.

I never asked for the spotlight. Never wanted the salutes or the whispers. My name is Daniel Reigns, and for…

No One Knew The Med Tent Girl Was Combat Medic—Until The General Declared, “You Saved the Whole Unit.

I remember the first time I walked into the med tent — the canvas walls flapping in the desert wind,…

End of content

No more pages to load